hetheringtonbc

Sunday, 27 July 2014

Friday, 25 July 2014

R J Hetherington:Healer Warrior

Robert John

Hetherington: Employment and Military Service

Record 1928 to 1964

Cpl.

Robert John Hetherington, RCAMC, 1944

Robert

John

Hetherington

Employment

Farm Labourer: Saskatchewan, 1928 to

1930

Orderly/Nurse: Prince Albert

Sanitarium, 1930 to 1935

Quartermaster: S.S. Kenora (CNR),

Vancouver, 1935 to 1937

Orderly/Nurse: Vancouver General

Hospital, 1937 to 1938

Orderly/Nurse: B.C. Penitentiary (New

Westminster), 1938 to 1940

Military Service

Reserve: Prince Albert Volunteers, 1930

to 35

Reserve: 11th Armoured Car,

Vancouver, 1938 to 1940

Enlisted: June 22, 1940; First

Battalion, New Westminster

Transfer: Royal Canadian Army Medical

Corps (RCAMC), October 28, 1940, Nanaimo

Recruiting: 30-04-1941

Transfer: Esquimalt Military Hospital,

November 1, 1941 - Orderly

Embarked: Halifax; June 15, 1942;

transfer16 General Hospital

Disembarked: Granoch, UK; June 24,

1942.

Leave to visit Ireland

Assigned to: 9 Field Surgical Unit;

March 11, 1944

Embarked UK: July 6, 1944; 11 Field

Dressing Unit; RCAMC

Disembarked France: July 8, 1944

Embarked NWE: June 29, 1945

Disembarked UK: June 29, 1945

Discharged: September 9, 1945

Reenlisted: March 20, 1954, X-ray

technician, Vancouver (Jericho), Prince Rupert and Holberg

Discharged: May 16, 1965

Awards:

Volunteer Service Medal and Clasp

France and Germany Star

Defence Medal

Robert`s Story: Healer -

Warrior

Robert

set

sail

from

Belfast, Northern Ireland

on

the

S.S.

Melita

on

a

farm/immigration

program

sponsored

by

the

CPR.

He

landed

in

Quebec

on

May

27,

1928

and

went

by

train

to

Saskatchewan

where

he

worked

for

two

years

as

a

farm

labourer

before

securing

a

position

at

the

Prince

Albert

Tuberculous

Sanatorium

in

1930.

He

meet

his

future

wife

Pauline

Krawchuk

at

the

“San”

and

also

joined

the

Prince

Albert

Volunteers

during this period.

After

his

marriage

in

1935

he

moved

to

Vancouver

where

worked

as

a

Quartermaster

on

the

S.S.

Kenora

(CNR).

In

1937

he

secured

work

at

the

Vancouver

General

Hospital

as

an

orderly/nurse.

In

1938

he

secured

a

job

as

an

orderly/nurse

with

the

B.C.

Penitentiary

Service

in

New

Westminster

and

joined

the

11th

Armoured

Car,

reserve unit in Vancouver.

He

maintained

both

positions

until

he

enlisted

on

June

22,

1940

in New Westminster with

the

First

Battalion.

On

October

28,

1940

he

was

transferred to the

Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps (RCAMC) in Nanaimo.

He was then transferred to Recruiting

from April 30,1941 to November 1, 1941.

He was then transferred to the

Esquimalt Military Hospital to work as an orderly.

While there, he requested a transfer to

active duty and was assigned to 16 General Hospital and embarked for

the UK from Halifax on June 15, 1942. He disembarked at Granoch, UK

on June 24, 1942. During his time in the UK he received additional

training and took leave to sight see and visit his brother Johnston

and his parents in Ireland.

On leave

On March 11, 1944 he was assigned to

the 9th Field Surgical Unit 11th Field Dressing Unit; RCAMC and

embarked the UK on July 6, 1944. He disembarked on Juno Beach on

July 8, 1944.

After landing in France, Robert travelled with the First Canadian Army as it fought its way north.

After landing in France, Robert travelled with the First Canadian Army as it fought its way north.

He cared for the wounded in field

hospitals as the Army closed the Falaise gap and liberated Dieppe.

He took leave in Amiens and continued north as the First Army moved

through the Pas de Calais and into Belgium.

By this time, First Army numbers were

badly depleted and were re-enforced by units from other countries.

RCAMC units were increasing engaged in

combat as they provided medical triage on the front line.

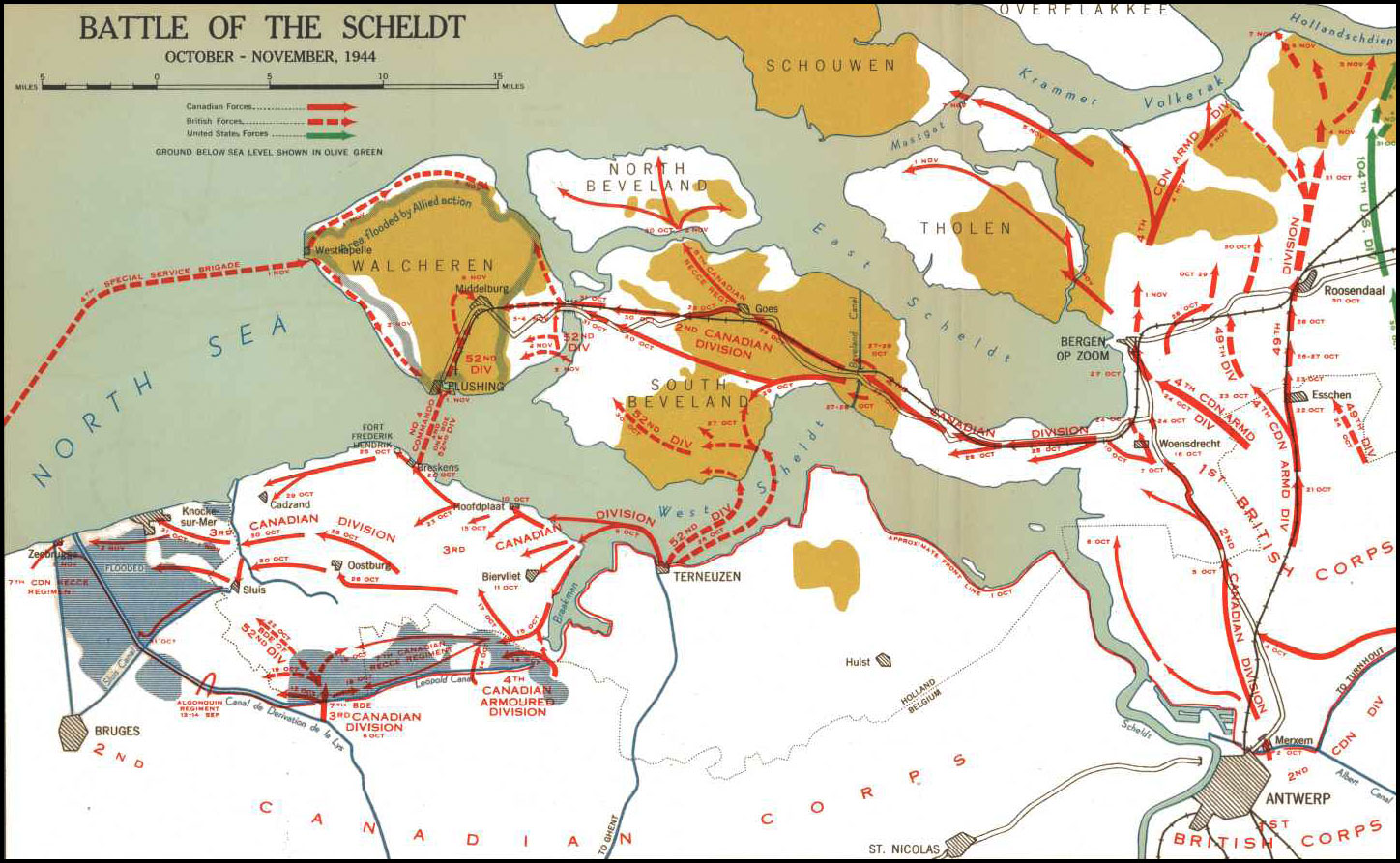

After the liberation of Antwerp on

September 4, the Army was given the task of clearing the entrances to

the port and Robert and his entire unit volunteered. He

subsequently, was part of the force that crossed and took the Leopold

Canal. After Leopold, his unit volunteered to fight with the

British Marine Commandos during the battle of The Scheldt. Where

three landing craft either broke down or were shot out from under him

before successfully landing.

He was involved in the

Walcheren Island campaign.

He told one funny story about

Walcheren, apparently, he had his pants to his knees behind a wall

when a machine gun opened fire on him. With the result that he was

force to run hid and return fire while struggling to get his pants

up!

Robert told another about treating a

newly captured English speaking German officer. After being treated

the officer asked if he could put his great coat on. Robert said yes

but luckily thought to check the pockets before giving him the coat.

It was fortunate that he did as there was a cocked Ruby pistol in the

pocket.

In November and December, Robert the

Canadian advance paused and Robert was stationed in home of Dutch

resistance fighter named Yette in Tilberg, Netherlands. During this

period he provided assistance to the Dutch underground as they

tracked down NAZI sympathizers. The picture below was taken at

Tilberg but is not of Robert. Robert was described by Yette as a

hero.

In the final days of the war Robert was

actively engaged in fighting in Germany.

It was here that he killed 3 young

German Hilter Youth who were defending their village. The boys

mother heard the fire and came running yelling `you killed may

babies, you killed my babies.` These experiences were to haunt

Robert for the rest of this life. Robert was in the field at war's

end and embarked NWE on June 29, 1945 and disembarked UK on June 29,

1945. He subsequently returned to Canada and was discharged on

September 9, 1945. In Canada he worked at a number of jobs including

as an Orderly at the BC Penitentiary in New Westminster. He

reenlisted on March 20, 1954, and worked as Army Orderly and X-ray

technician in a number of locations including: Vancouver (Jericho),

Prince Rupert and Holberg. He was finally discharged

on May 16, 1965 and eventually received a military disability

pension. He died in his bed in January, 1976.

Descriptions of the role the RCAMC Field Dressing Station

Below are descriptions of RCAMC #8 FSU and Field Dressing Station 10 service at Walcheren (RJH was in #9 FSU - FDS 11 and faced similar challenges):

“We had to crawl two hundred yards on our bellies with the exploding ammunition [from a stricken assault vehicle] shooting at us from one side and the Germans from the other. We finally reached the [No. 10 FDS] tent and found that the Staff Sergeant had organized a rescue team and was going down in that blazing mess and bringing out the survivors. One of the medicals went inside of an exploding Alligator to reach a wounded Commando. He was blown half in two by a mortar bomb. For the next half hour we lay on our faces in the sand dressing wounds, stopping hemorrhages and splinting fractures. Constant explosions were blowing sand over us as we worked. Our heads were retracted down in our helmets until the edge of the damned things almost reached our shoulders“ (John Hillsman, quoted in Bill Rawling, Death Their Enemy: Canadian Medical Practitioners and War, 2001, p. 211).

“8 Canadian Field Surgical Unit, RCAMC who were with

the British Commandos when they went in on Walcheren Island.”

"...For the first 48 hours the beachead where the medical units were established was under constant and heavy shell-fire. There were no buildings or shelters available of a safe nature to perform major operations and to properly look after the patient after operation. The area was honey-combed with land mined which could not be detected and removed and the tentage was surrounded by large bomb craters and shell holes containing numerous German prisoners, ammunition, petrol and demolition charges. After the first 24 hours a gale sprang up from the North Sea which, at times, reached a velocity of 50 miles per hour and rain was constant, mingled at times with hail.....

In all 54 soldiers were operated upon, 22 which were major operations and, by some miracle of chance, none of these were abdomens.”

"...For the first 48 hours the beachead where the medical units were established was under constant and heavy shell-fire. There were no buildings or shelters available of a safe nature to perform major operations and to properly look after the patient after operation. The area was honey-combed with land mined which could not be detected and removed and the tentage was surrounded by large bomb craters and shell holes containing numerous German prisoners, ammunition, petrol and demolition charges. After the first 24 hours a gale sprang up from the North Sea which, at times, reached a velocity of 50 miles per hour and rain was constant, mingled at times with hail.....

In all 54 soldiers were operated upon, 22 which were major operations and, by some miracle of chance, none of these were abdomens.”

“...One cannot end a report of this nature without a

few words of intense admiration of the work done by #10 FDS in

connection with the #8 FSU. Under the most appalling conditions the

post-op care of our patients by this unit left nothing to be desired.

No patient in this beachead suffered from lack of care if it was

humanly possibly by any effort on their part to give it to him.

...The work of these stretcher-bearers in, quickly and efficiently,

carrying the patients to and from the operating theatre in the face

of a terrible gale, blowing wind, hail, and sand, was one of the

brightest of the whole operation from the medical side."

R J Hetherington: Healer/Warrior - gone but not forgotten

Sunday, 3 November 2013

Mosey's Road Home

“May you have a long and

happy life.”

Mosey's road

home

Written by: Thomas John McClean

Hetherington, with the assistance of Andrew and Gary McClean

Hetherington, September, 2013.

This is a story about “wee folk”,

fathers and sons and a place in Ireland. It is based in fact and was

told to me by my father, Robert John McClean Hetherington (Robbie).

Robert John McClean

Hetherington (Robbie)

My father was a story teller, and as

such may not have let the truth stand in the way of creating a good

yarn. I apologize if I misrepresent the true nature of the people

described. My story is based on the 52 year old memories of a child.

I leave it to the reader to judge its truth.

When I was a boy my father told me

stories about the place where he was born -- a troubled place filled

with family members who exist only in the memories of their loved

ones -- people brought to life in his stories.

The date was November 1960, the year

before the death of his grandparents, and Robbie Hetherington and his

9 year old son Tommy sat in the living room of their house at 925,

6th Street in New Westminster.

925 6th Street, New

Westminster

Robbie was in his favourite chair next

to the fireplace. The smell of Erin More pipe tobacco filled the

room with a pungent odour that Tommy always associated with his dad.

These were special times listening as his dad told stories about the

“Old Country.”

Robbie took several short pulls on his

pipe to stoke the embers, exhaled and said, “ Aye, the last

Hetherington still on the hill is my sister Eileen. The rest have

moved away because of troubles and better pensions. Was a time when

Creggan Hill was home to the Holmes, McCleans, Johnstons and

Hetheringtons.” “Most are gone now to the other side of the

border – my parents and William James moved to County Down.” The

Johnstons are the only ones that remain there in any real numbers.

With everyone gone the house was turning into a pile of rubble,” he

said.

Robbie was born on Creggan Hill in 1910

in a house near Raphoe in County Donegal. His life was to be shaped

by civil war, immigration to Canada in 1928, heroic military service,

and his later years, a thyroid problem, sleep apnea and bouts of

alcoholism. He was a spiritual man and a Mason, and not really a

church goer. He believed in always doing one’s duty, and the trauma

he experienced from doing his, damaged his soul. He died at age 65.

His ashes are spread in the garden of St. Mary's Anglican Church in

New Westminster.

The land where Robbie was born was

initially leased by the Hetheringtons from the Church of Ireland, and

eventually purchased in 1905. Located in Upper Glenmaguin, it is best

accessed from a narrow road that ends at the crest of Creggan Hill.

The Hetherington plot is straight ahead.

“Aye”, Robbie started again,

sipping on a warm cup of tea. “Was a time when we were all related

there. Before the automobile we got around by foot and that meant

that there weren’t many people that you could marry -- so we

married each other, like the royal family,” Robbie said with an

impish grin. “You can see that in our family tree, McCleans

married Hetheringtons for several generations. “It’s why our

last names are McClean Hetheington,” he said in a matter of fact

tone.

“There were two McClean families on

the hill, and the Mosey McClean branch had a reputation for being a

bit wild and strange. A lane, we called “the street” passed in

front of Mosey’s place,” he explained. “McClean's had a garden

immediately across 'the street' from their house and I remember

picking gooseberries there - they were terribly sour.” he said

puckering his lips.

Mosey McClean House with

child in door frame

He continued, “the McCleans could

hear a piece of music once and then play it from memory. Some say

they could read minds.”

“But when it came to ‘the gift’,

the person I learned the most from was William James,” he said.

“When I was growing up, William James lived with us, at least he did

when we weren't all separated because of work away and The

Revolution,” Robbie said with a deep sigh. “I had to stop going

to school at age 10. They turned Glenmaquin School into barracks for

the Black and Tans and that was the end of my schooling.”

After a pause, “William James was a

fine man with a shovel. One time he dug a drainage ditch down “the

street” by hand,” Robbie said, obviously impressed.

William James and Andrew

McClean Hetherington

After a sip of his strong dark tea,

Robbie reached into his shirt pocket and pulled out an old

photograph, he passed it to Tommy who examined it closely.

McClean Hetherington House

“The house was built of stones, from

fist sized to arm sized, gathered from the earth ‘round about.

There was no money for mortar so we used local 'blue clay'. This

clay is found underneath the turf. I remember being out with my Dad

clearing out a sheugh, and he showed me the gravel layer with the

blue clay on top. This he said was from the time of Noah and the

Great Flood. He was a very religious man,” he paused, puffed and

continued.

“The clay was fine as a binder as

long as it was dry, but we had to whitewash once a year to waterproof

it, and we had to tar the bottom foot or so to help prevent rising

damp,” he said gently waving his pipe in a painting motion.

“As you can see the house was a

single story affair. The thatch was made of rushes taken from the wet

ground in front of the house. We usually kept a cow in the byre on

the left, next was the main room. Everything happened in the main

room. It was our living room, bedroom, and kitchen. There was a

hearth with a crane and crook for cooking, with a cast iron kettle

permanently on the boil. Never was a man turned away without the

offer of hot tea. My dad and William James never drank tea from a

cup or mug, it was always from a bowl. They said it was to keep

their hands warm.” He paused again sipped his tea, briefly closed

his eyes as if searching his memory and said, “there was a table, a

couple of chairs, a homemade bench to sit on, and a dresser to store

a few plates and mugs. This dresser formed a bit of a wall, and with

another bit of thin plywood, created a small room with a bed. Along

the far wall beside the hearth was my parents’ bed which had a

curtain to keep the draughts out. Not too much room for us all and

sometimes I'd just go out into the fields to look at the stars and

find peace,” he said with a far off look in his eyes.

As if waking from a dream, he

continued, “there were no house numbers on the hill, and the local

postman had the job for life and knew everybody. When I was back

during the war, the postman was Henry Gallagher who was based at

Knockbrack post office 3 or 4 miles away. The house was at the end of

his round and he would have his tea and a piece of homemade bread and

jam before heading back. Occasionally, he'd come up to the house in

the evening with his melodeon for a bit of a ceilidh. Aye, was always

was good to hear music on the hill, made it magical: music, laughter

and the warm glow of the hearth,” he paused and rubbed his eyes

with a hankie that he drew from his pants pocket and blowing his

noise said, “Aye, it was grand”.

Replacing the hankie in his pocket and

referring back to the picture he continued, “You see the hawthorn

tree beside the house? As a boy I would pick the unripe haws and

with a piece of weed with a hollow center use it as a pea shooter, I

remember one time I hit my brother Johnston with a haw and it caused

quite a row. “

Johnston and Robbie

1943/44

Robbie paused a took a draw on his pipe

which had gone out due to the length of the story so he fished a

match box out of his small black leather tobacco bag, struck a match

on the striking paper on the side of the box and put it to the bowl.

After a couple of draws the tobacco started to glow and after one or

two more puffs he continued putting the box and bag on the table.

“The blackthorn bush is related to

the hawthorn and both have magical powers. Fairy folk are said

to guard blackthorn trees and will not let anyone cut branches - if

you do you will be cursed with bad luck. Farmers would plough around

a blackthorn so as not to annoy the fairy folk,” he said earnestly.

“I have seen instances of a single blackthorn in a field is

undisturbed by the farmer. The wee folk seem to like the thick,

impenetrable thorn bramble, may be because it hides the entrances to

their houses,” Robbie said knowingly.

After a short pause, he started, “many

years ago, Moses McClean, stumbled out of the Red Hand Pub in Raphoe

and into the darkness.“

Mosey

McClean

“He was a young man then, a grand man and very well liked, when wasn't drinking. Almost named you after him,” Robbie said to Tommy, “but your mum didn't think a name like Moses was quite right for a Canadian lad, so we named you Tommy instead.” “She said it was to remember her uncle Tom Achtimechuck but to me you were named after my brother in – law Tommy Johnston.”

This story is about Mosey before he

took the pledge,” Robbie added as if to defend the man's honour.

“Mosey was a bit of a dare devil always tempting fate with some

kind of antic. I will always remember him, on his bicycle careening

erratically down the Creggan lane, bouncing off the seat, barely

avoiding collision and laughing like a mad man as he left for the

pub!”

Suddenly Robbie looked pensive, “he

met a sorry end, he did. He left Raphoe for Scotland......... they

found his shoes on the shore and body in Kirkcaldy harbour. Sometime

later both his sons, Willie and Sam drowned in the same harbour.

People say they were suicides........” he said in a hushed tone.

After another draw on his pipe he

continued, “but that night as the barman locked the door behind

him, Mosey prepared for the long walk down the Convoy road to Creggan

lane and then up the hill to his bed. He mumbled to himself, I need

to drink less or find a place to sleep in town, I am sick of this

long walk, especially at night. Luckily, a full moon was just

appearing on the horizon. Good, I’ll not have to walk in the dark,

he thought as he buttoned up his ragged coat. Fortunately, he had

managed to buy the remnants of a bottle of Bushmills from the

barkeep. Now penniless but with fortification against the cold night

air he stumbled off across The Diamond.”

“He avoided the graveyard at St.

Eunnan’s, Mosey never felt comfortable around graveyards especially

at night. His sister had told him that was because he was afraid of

going to hell because of the trouble he caused by his fondness of

“drink”.

“By the time Mosey got to the Creggan

lane he was really starting to get tired and was tempted to lay

down for a sleep. Instead he reached in his pocket and pulled out

the partially consumed bottle and took a long pull. That will help

me get home he thought as a stumbled up the narrow lane. After a

while he walked past the Johnston house and eventually reached the

end of the road. He stopped and finished his bottle. Throwing the

empty into the hedge he looked across the fields and saw Hetherington

place straight ahead. He noticed a small light flickering in the

window. I wonder if Andrew or William James were up? They are not

big drinkers but may be they'll invite me in for a drink, or at least

a cup of tea, he thought, and started walking toward the dimly lit

window. The field was very mucky and each step made a sucking sound

as his foot lifted from the muck and a squishing sound as it went

back down again. Suck, squish. suck, squish, he plodded onwards,

until he found himself it the door of the Hetherington house. He

knocked.

Unfortunately, it was not Andrew or

William James who answered but his sister, Maggie. “Whose there”

she shouted from behind the door. “Your brother,” Mosey

responded. The door opened and a woman in a nightshirt stood in the

door frame. What are you doing up in the middle of the night, you

been drinking again? She asked in an angry tone. “May be just a

wee drop” Mosey responded, looking down at his feet. “I told

you before, don’t come around when you’ve been drinking, I’ll

have none of that.” Go home and go to bed,” she said, slamming

the door in his face.

Maggie

McClean Hetherington

Disappointed with his reception (and

the absence of even the of a cup of tea) he turned and started to

walk home. After a few paces, he became dizzy, lost his balance, and

fell face first into the clabber. Too tired to get up he bundled up

in his coat and rolled up near the hedge and closed his eyes. He

wasn’t sure how long he lay there - he must of fallen asleep.

Robbie paused and tapped hot ashes

from his pipe into the fire. Once empty he put the pipe into an

ashtray on the metal TV tray beside the chair.

He started again, Mosey was awakened by

a tugging on his boots. For a moment he thought he’d made it home

and his wife, Bella was putting him to bed but then he remembered

where he was and opened his eyes to discover a small creature trying

to pull to his boots off.

Bella McClean (Orr)

playing her melodeon

“The wee folk are excellent

cobblers,” Robbie said as an aside, “they really can not resist a

worn pair of boots.”

Suddenly, and with more coordination

that he demonstrated in years, Mosey shot up and grabbed the being's

leg. “Got you, you thieving little devil” he cried. “You’ll

not have my boots”, he said tightening his grip.

The creature responded, “forgive me

kind sir, I saw you were asleep and I was only trying to take your

boots off so you’d be more comfortable”.

Then it dawned on Mosey, he captured a

wee person, his mind raced to determine how he could best take

advantage of the situation. “I’ll not let you go you evil little

thing, I ought to murder you for trying to steal my only pair of

boots” he exclaimed.

“No, no, no don’t hurt me,”

responded the little man, “let me go and I will give you great

wealth.”

“Great wealth”, Mosey responded,

“what do you mean by that?”

“Let me go and I’ll fill your

pockets with gold,” the little man said.

“Show me”, Mosey responded.

Still held upside down, the little man

pointed to the base of a blackthorn bush. “Look there,” he said,

“and you’ll have gold a plenty.” Mosey looked and saw a small

pot of pebble sized gold nuggets. “Boys oh”, he said, picking up

the pot with his free hand, his mind racing with excitement.

“Now let me go,” said the fairy

man. “You’ve got gold a plenty - you’ll not need me.”

Mosey responded, “I am a man of my

word,” and he freed the wee one from his grip. Quickly it vanished

into the tangle of blackthorn roots.

“I am rich, I am rich,” Mosey sang

to himself as he filled his coat pockets with nuggets, I’ll have

whisky to spare, he thought. Still drunk and pockets full, he

stumbled home. Once there, he passed out on his bed.

He was awakened by the dawn. He opened

his eyes and remembered his good fortune of the night before. “I

am rich, I am rich,” he said to himself over and over again. But

when he got up and retrieved his coat he sadly found his pockets

sadly empty. Pulling his pockets out he discovered that each one had

a hole in it. Gold must have fallen out as I walked, he thought. He

then went to the door and looked down the street.

Sure enough there was a zig-zagging

trail of gold nuggets leading to the Hetherington place. Relieved,

he went back inside to get a bag. I'll retrace my steps and put the

gold in this bag, he thought. As he stepped out of the doorway the

first rays of sun appeared from over the horizon and touched the

ground. He was horrified when he saw that as the sun touched each

nugget it transformed into an ordinary wee pebble! His now aching

head filled with rage, he had been made a fool of and duped by the

little man. He began to curse and as he did he thought he heard

faint laughter from the hedge. Sure enough his exploits of the night

before had a very different look in the clear light of day. In the

end all he had was a mucky coat, bag of pebbles and a very sore head.

This story had

stayed in Tommy's mind all of this life. How much of this is true he

wondered? So, in 2012, at the age of 61 he and his son Matthew, then

18 set off in search of “leprechauns” (that is what they call the

wee folk in American films) . While they discovered many things

during their odyssey, they were not able to verify the truth of the

story nor did they manage to find or capture any leprechauns (in

spite of placing traps baited with old boots). They were however able

to find and document some of the places mentioned in the story. The

a future blog post will archive their findings.

Saturday, 26 October 2013

Final resting places

I am not sure why Robbie's parents and uncle left Creggan. I suspect, political upheaval, a poor economy, and societal changes resulting from the Irish revolution were undoubtedly keenly felt by the Hetherington's of Upper Glenmacquin. I also imagine the hardships of living with a well for water and out door toilets, etc. became increasing difficult to manage with age. These factors, and perhaps better seniors care, resulted in end of life aging in the UK and burial at the Whitechurch Cemetery, Ards. They may have also simply wanted to eternally rest under the British flag and not the Irish Tri-colour?

Whitechurch Cemetery

Margeret McClean and Andrew Hetherington

Andrew, Maggie and Robbie at house 1944

Headstone at Ards

William James Hetherington

William James and Johnston Headstones at Ards

Robbie, Edith (Johnston's wife) and Johnston Hetherington 1964

Edith Hetherington headstone at Ards

Matt visiting Graveyard at St. Eunan's, 2012

Not sure of relationship (Nathaniel?)

Not sure of relationship (Nathaniel?)

Not sure if relationship?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)